But hey, one day, the thing might really be something, so get in on the ground floor while you can.

www.esquire.com

The F-35 Strike Fighter Continues to Be a Massive Waste of Taxpayer Money

Charles P. Pierce

7 - 9 minutes

With everything else that's going on, we've lost track of one of the shebeen's favorite obsessions — the F-35 strike fighter, aka The Flying Swiss Army Knife, aka The Great Money Pit in the sky. Fortune (via Yahoo Finance) would like you to know that, while the F-35 continues to be an historic lemon, Lockheed-Martin has managed to make some sweet, sweet lemonade out of it.

Almost since the F-35 program was announced in 2001, it has been the symbol of America’s dysfunctional military-industrial complex. The jet is 10 years behind schedule for final approval and almost 80% over budget, its production repeatedly stalled by defects and miscalculations...Nonetheless, Germany ended up buying nearly 40 of the jets, at a reported cost of $8 billion. Soon after Scholz’s speech, Canada announced that it wanted 88 planes. As the war in Ukraine dragged on, Greece, the Czech Republic, and Singapore all expressed interest in the F-35. And this came on the heels of massive new orders in 2021 from Finland and even the famously neutral Swiss.

One of the defects was that the plane had trouble working in the rain. Nevertheless, Lockheed Martin is selling these planes with both fists overseas.

The program is also a measure of the health of Lockheed Martin, the largest weapons company that has ever existed. Lockheed brought in about $66 billion in revenue in 2022, virtually all of it for arms. (The company makes missiles, missile defense systems, warships, and a host of other combat aircraft, among other products.) It sits at the top of an industry that’s more important to national security than ever: About 58% of the Pentagon budget went to private contractors in 2020, the highest share in 20 years, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Ultimately, the F-35 is a test case of Lockheed’s and the Pentagon’s ability to deliver results. Put simply, the calculus runs like this: Either the F-35 was a massive waste of resources—the worst-ever example of the defense industry overpromising and underdelivering—or it was a savvy long-term investment that gives America and its allies a substantial advantage over their enemies.

If that's not the definition of what Rep. Barney Frank used to call "military Keynesianism," I don't know what is. Sure this boondoggle has cost the sucke...er...taxpayers a few trillion dollars that could have been spent elsewhere, but, hey, one day, the thing might really be something, so get in on the ground floor while you can. Oh, and by the way, two decades of glitches were exactly what we needed to make great leaps skyward.

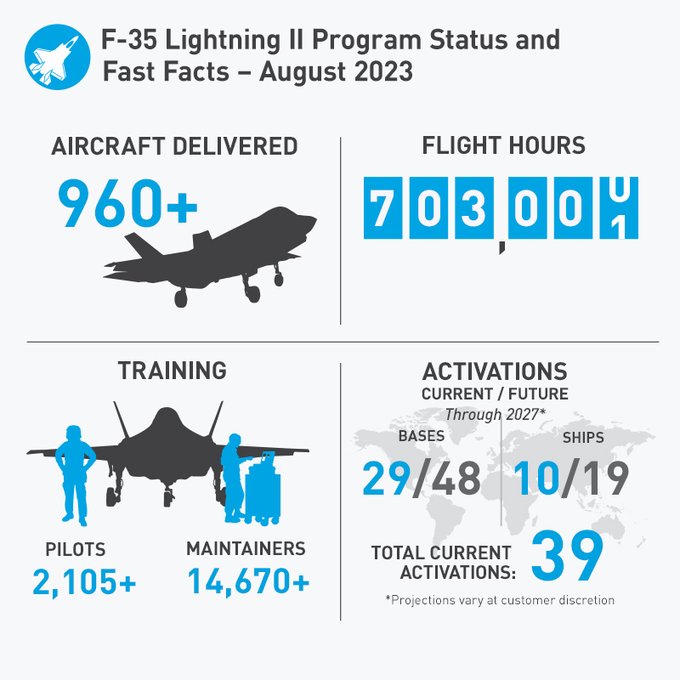

Contrary to popular belief...the F-35 does work. Lockheed has delivered about 960 of the jets so far, with about 630 going to the U.S. military—and the plane has performed effectively in combat multiple times. The F-35 has yet to face protracted battle against a sophisticated foreign military. But if or when it does, its design incorporates technological breakthroughs that could confer a huge edge in battle, enabling it to evade detection while linking U.S. and allied forces in a data-sharing network that could outmaneuver and overwhelm an enemy. The F-35 is indeed plagued by cost overruns and delays. But those problems are inextricably linked to the advances that have gradually won over pilots and governments—advances that until recently have, almost literally, flown under the radar.

Great. Here's what some of those advances have cost you, me, and the rest of the country.

In the late 1990s, Lockheed won the Pentagon contract to build the Joint Strike Fighter. But the program was a fiasco almost from the start. Lockheed and the Pentagon immediately slammed into technological hurdles. The F-35 version for the Marines, which was designed to take off vertically rather than from a runway, proved to be exceedingly difficult to get right. (The program eventually abandoned the uniform-chassis idea.) By late 2009 Lockheed had delivered only four of 13 promised test aircraft. The number of labor hours it took to build each plane had ballooned by about 50%. The effort was also plagued by the Pentagon’s decision to make the program “concurrent,” which meant that Lockheed was contracted to keep building F-35s even as it invented capabilities that impacted their design—which in turn required the government to pay for constant upgrades to earlier versions of the jets.

Ah, good old Uncle Sucker, always good for a bailout, as long as he doesn't use that ejector seat, I guess.

Over the next decade, the F-35 continued to falter in very public ways. In 2015, it performed poorly in a dogfight against older F-16s. Its engine, made by subcontractor Pratt & Whitney, burned so hot that it turned atmospheric sand and grit into glass inside the plane, hurting performance and requiring redesigns. And yet, as new capabilities were added to the F-35, it became apparent that the engine wasn’t powerful enough to provide energy to cool the plane’s internal systems. Maybe most frustrating, the F-35 required several million lines of software code to operate. That code, like all code, turned out to be buggy and in need of constant rewriting. By 2021, the cost of the F-35 had nearly doubled—overall outlays for the project, originally estimated at $233 billion for the first 20 years, had in fact reached $416 billion.

The piece then goes to a place of wonderment at the technological marvel that all these overruns hath wrought, before returning once again to what the marvel has cost the rest of us.

But the system’s long, slow development illuminates the core of Lockheed Martin’s business strategy. The company is patient, quietly matching its engineering talent against the desires of the Pentagon until it achieves the right fit. It’s sort of like building a house when the client keeps asking you to add new rooms and, along the way, to invent a new kind of air-conditioning system. At the same time, Lockheed endures public humiliation in the town square of congressional hearings. One hangover from the F-35’s 2010 budget crisis: Every year, Congress’s General Accounting Office publishes an audit of the program, which inevitably (and accurately) reports that the F-35 is late and over budget—stoking more ugly headlines.

Every improvement, it seems, begets expense, delays, or both.

You think? This is the thinking behind the derisive nickname, The Flying Swiss Army Knife. Originally, the F-35 was supposed to be a replacement for the A-10 "Warthog," a kind of flying tank beloved. by infantrymen. Interservice rivalries and the limitless military-industrial troughs soon pushed it beyond its original mission of close air support. All of the services wanted their own version. (The Marines wanted a vertical takeoff plane.) Now, if you listen to the people making a buck off it, through grotesquely expensive trial and error, Lockheed Martin has stumbled into inventing the Starship Enterprise. Don't think about all the places all this money would have done the most good. Just keep writing the checks. Lockheed Martin has your best interests in mind.