Ezt ahhoz, hogy próbálták a britek csökkenteni a károkat:

Colonial Biopolitics and the Great Bengal Famine of 1943

(félkövér kiemelések tőlem)

..."

Responsibility of the colonial authorities

The role and responsibility of the British government during these crisis months were always highly questioned.

The interventions by the government of Bengal in the province’s wholesale rice markets in 1942 and 1943 triggered the crisis. Greenough (1982) calculated that even after deducting the losses due to the halt of Burmese imports, the Midnapur cyclone, flood, and crop disease due to pest attack (see Padmanabhan, 1973), 90% of the usual supply of rice was available in 1943. There was also no deficiency of rice in Bihar, Orissa and Assam indicating that there should not have been any shortages in Bengal provided the surplus grain was accurately circulated, which the Indian Government failed to accomplish (Law‐Smith, 2007).

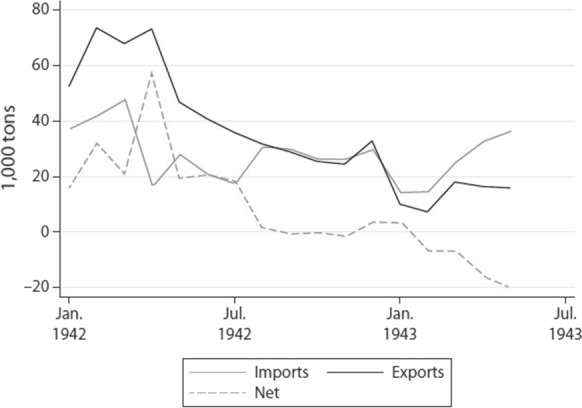

During the famine, the utilitarian principles and profit-seeking attitude of the British administrators dictated that for Britain to satisfy Indian demands, shipping and supplies had to be sourced for British soldiers fighting the Germans at that time. Also, supplying food to Indian civilians would have risked British civilian food supplies. The total amount of wheat harvested in the British Empire during the 1943–1944 year was 29 million tons, but the war cabinet strategically preserved it for the future. So, despite Bengal’s rice shortages, the British Empire had sufficient wheat to send to the famine victims (Mukerjee, 2014). Even in 1943, at the height of the famine, the UK imported 26 million tonnes of food and raw materials for its civilian population, creating a stockpile of 18.5 million tonnes at the end of the year. The Indian Central Food Department intended to set up a central purchasing organization, but the government mismanaged the situation and did not inform the surplus provinces about setting up procurement machinery until the end of January 1943. Bengal expected delivery of 350,000 tonnes of rice between April 1943 to March 1944 from neighboring states, but, unfortunately, received only 25,000 tonnes of rice supplied by Orissa (Law‐Smith, 2007). The total imports and exports during 1942–1943 are shown in Fig. 3.

Bengal’s rice trade, 1942–1943.

(

Source: Ó Gráda, 2015, p. 59)

It is simplistic to ascribe all the failures by putting the entire blame only on the British government. As mentioned earlier, there were different other complex issues like market failures, policy failures, malfeasance by government agencies, as well as different unethical practices by private companies. A more nuanced view also acknowledges the role of Punjab, which had a surplus of food grains in 1943–1944. There was an ongoing politics between the Punjab peasants’ lobbies and the ruling party that utilized the wartime soaring prices of food grains to compensate for the losses the Punjab peasantry had suffered earlier during the economic depression of the 1930s. The government sought to safeguard its rural vote bank by publicly advocating for allowing the wartime grain markets to operate on a laissez-faire basis (Yong, 2005). Many peasant leaders in Punjab encouraged farmers to resist the procurement of food crops by government agencies at a fixed price. This wartime prosperity of Punjab specifically when Bengal suffered helped to reproduce uneven development within India.

Official declaration and news of this ‘British- induced famine’ were deliberately suppressed from the people of Bengal to serve British interests. In August 1942, Bengal’s chief finance minister, Fazlul Huq, warned colonial authorities of a potential famine because of these policies. He was ignored by the British Governor of Bengal, John Herbert. At the same time, press regulations were employed to interrupt the circulation of any information from Bengal. This was not the first time the government have concealed news of the famine. While researching British responses to famine throughout the last 200 years, Sasson and Vernon (2015) discovered that famine news was not extensively disseminated in the British press and that the key concern was the negative impacts on tax reduction, as noted during the 1770 Bengal famine as well."...

..."

The British generally perceived their colonial subjects as childlike, needing guidance in their every step of how to behave properly. The Indian working classes were believed to lack intellect and were always driven by bodily passions. When the Delhi government sent a telegram to Churchill depicting the horrible devastation generated by the famine and briefed him about the total number of deaths, his response was “Then why hasn't Gandhi died yet?” (quoted in Choudhury, 2021, p. 4). Churchill even claimed that the Indian population were the beastliest in the world after the Germans, the famine was created by themselves caused by overpopulation, and that Indians should pay the price for their negligence (Collingham, 2012). These statements paint a coherent picture of how the British colonial authorities marginalized their colonial subjects and reified racial exclusion."...

Nemááár? De.