Eredetileg karácsonyi parádé volt NYCben, jövőre lesz százéves. 1942-44 között szünetelt, mert kellett a helium meg a gumi stb a háborúhoz.Azt hiszem Philadelphiában volt az első ilyen hakni.

-

Ha nem vagy kibékülve az alapértelmezettnek beállított sötét sablonnal, akkor a korábbi ígéretnek megfelelően bármikor átválthatsz a korábbi világos színekkel dolgozó kinézetre.

Ehhez görgess a lap aljára és a baloldalon keresd a HTKA Dark feliratú gombot. Kattints rá, majd a megnyíló ablakban válaszd a HTKA Light lehetőséget. Választásod a böngésződ elmenti cookie-ba, így amikor legközelebb érkezel ezt a műveletsort nem kell megismételned. -

Az elmúlt időszak tapasztalatai alapján házirendet kapott a topic.

Ezen témában - a fórumon rendhagyó módon - az oldal üzemeltetője saját álláspontja, meggyőződése alapján nem enged bizonyos véleményeket, mivel meglátása szerint az káros a járványhelyzet enyhítését célzó törekvésekre.

Kérünk, hogy a vírus veszélyességét kétségbe vonó, oltásellenes véleményed más platformon fejtsd ki. Nálunk ennek nincs helye. Az ilyen hozzászólásokért 1 alkalommal figyelmeztetés jár, majd folytatása esetén a témáról letiltás. Arra is kérünk, hogy a fórum más témáiba ne vigyétek át, mert azért viszont már a fórum egészéről letiltás járhat hosszabb-rövidebb időre.

-

Az elmúlt időszak tapasztalatai alapján frissített házirendet kapott a topic.

--- VÁLTOZÁS A MODERÁLÁSBAN ---

A források, hírek preferáltak. Azoknak, akik veszik a fáradságot és összegyűjtik ezeket a főként harcokkal, a háború jelenlegi állásával és haditechnika szempontjából érdekes híreket, (mindegy milyen oldali) forrásokkal alátámasztják és bonuszként legalább a címet egy google fordítóba berakják, azoknak ismételten köszönjük az áldozatos munkáját és további kitartást kívánunk nekik!

Ami nem a topik témájába vág vagy akár csak erősebb hangnemben is kerül megfogalmazásra, az valamilyen formában szankcionálva lesz

Minden olyan hozzászólásért ami nem hír, vagy szorosan a konfliktushoz kapcsolódó vélemény / elemzés azért instant 3 nap topic letiltás jár. Aki pedig ezzel trükközne és folytatná másik topicban annak 2 hónap fórum ban a jussa.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Talán esetleg ne kepekbol akarjatok okoskodni, hanem pl vegignezed a tucatnyi teljes streamet a praderol YTon, es akkor kiderul, szinte teljesen fekete egyetemek is vonultak...

"...De ezek csak pár kép, többsége is inkább a figurákat mutatja. Ne vonjunk le ezek alapján semmit mert pl én ázsiait nem is láttam..."

Na ez várható volt...

apnews.com

apnews.com

Ex-officer Derek Chauvin, convicted in George Floyd's killing, stabbed in prison, AP source says

Former Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin has been stabbed by another inmate at a federal prison in Arizona where he's serving time for the murder of George Floyd.

Te nem hallottál még a Macy's Thanksgiving Parade hagyományról...?

Hat így különösen röhejes az a mellény, amivel osztod itt rendszeresen az észt Amerikáról...

Már nem azért, de miért kellene mindenkinek tudni a New York-i belterjesség összes dolgáról? Ha nem hallott róla, akkor már semmit sem tud Amerikáról?

Why America Abandoned the Greatest Economy in History

Opinion by Rogé Karma • 20hMARKETS TODAY

INX▲ +0.06%

DJI▲ +0.33%

COMP▼-0.11%

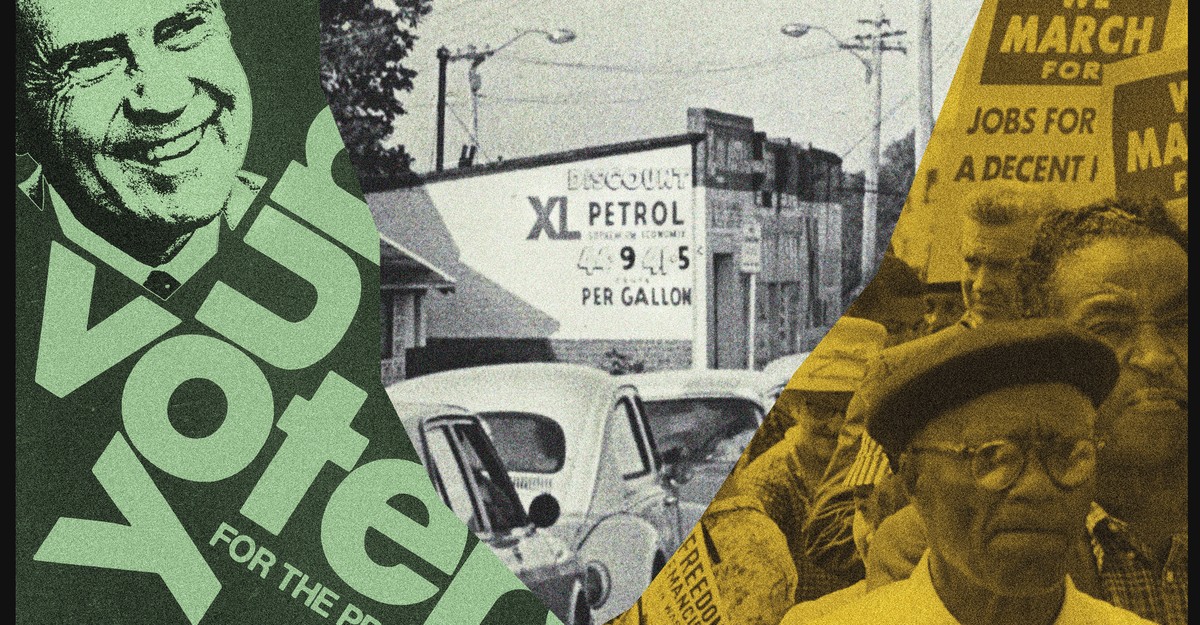

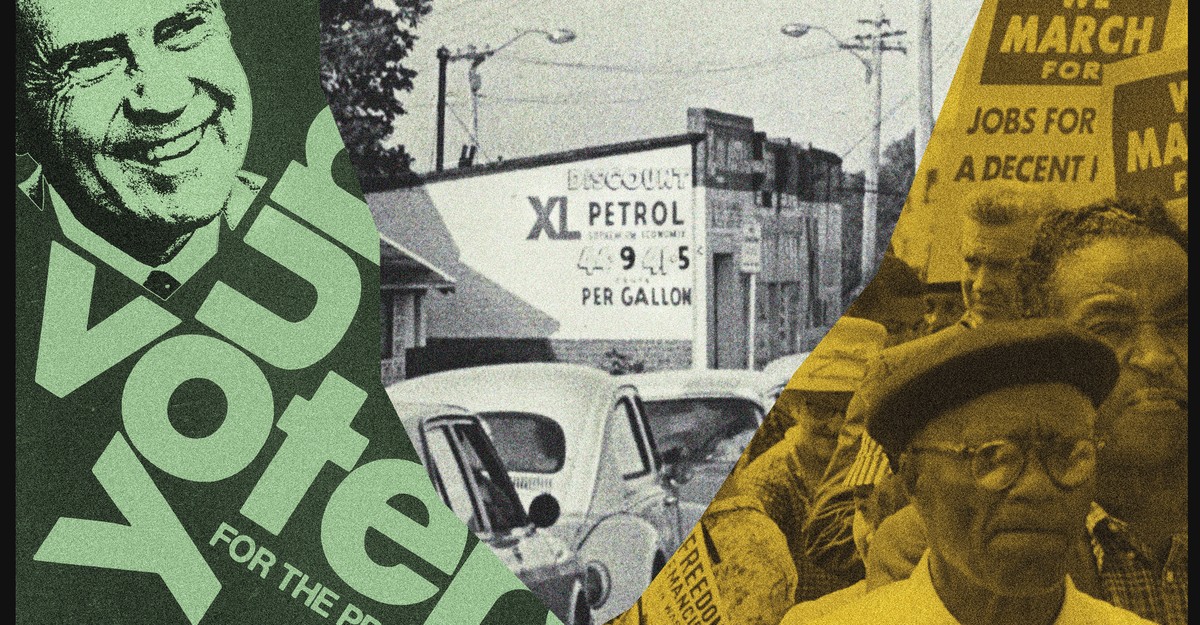

Why America Abandoned the Greatest Economy in History© Illustration by The Atlantic.

Sources: Barry James Gilmour / Getty; Kean Collection / Getty; Library of Congress / Getty.

If there is one statistic that best captures the transformation of the American economy over the past half century, it may be this: Of Americans born in 1940, 92 percent went on to earn more than their parents; among those born in 1980, just 50 percent did. Over the course of a few decades, the chances of achieving the American dream went from a near-guarantee to a coin flip.

What happened?

One answer is that American voters abandoned the system that worked for their grandparents. From the 1940s through the ’70s, sometimes called the New Deal era, U.S. law and policy were engineered to ensure strong unions, high taxes on the rich, huge public investments, and an expanding social safety net. Inequality shrank as the economy boomed. But by the end of that period, the economy was faltering, and voters turned against the postwar consensus. Ronald Reagan took office promising to restore growth by paring back government, slashing taxes on the rich and corporations, and gutting business regulations and antitrust enforcement. The idea, famously, was that a rising tide would lift all boats. Instead, inequality soared while living standards stagnated and life expectancy fell behind that of peer countries. No other advanced economy pivoted quite as sharply to free-market economics as the United States, and none experienced as sharp a reversal in income, mobility, and public-health trends as America did. Today, a child born in Norway or the United Kingdom has a far better chance of outearning their parents than one born in the U.S.

This story has been extensively documented. But a nagging puzzle remains. Why did America abandon the New Deal so decisively? And why did so many voters and politicians embrace the free-market consensus that replaced it?

Since 2016, policy makers, scholars, and journalists have been scrambling to answer those questions as they seek to make sense of the rise of Donald Trump—who declared, in 2015, “The American dream is dead”—and the seething discontent in American life. Three main theories have emerged, each with its own account of how we got here and what it might take to change course. One theory holds that the story is fundamentally about the white backlash to civil-rights legislation. Another pins more blame on the Democratic Party’s cultural elitism. And the third focuses on the role of global crises beyond any political party’s control. Each theory is incomplete on its own. Taken together, they go a long way toward making sense of the political and economic uncertainty we’re living through.

“The American landscape was once graced with resplendent public swimming pools, some big enough to hold thousands of swimmers at a time,” writes Heather McGee, the former president of the think tank Demos, in her 2021 book, The Sum of Us. In many places, however, the pools were also whites-only. Then came desegregation. Rather than open up the pools to their Black neighbors, white communities decided to simply close them for everyone. For McGhee, that is a microcosm of the changes to America’s political economy over the past half century: White Americans were willing to make their own lives materially worse rather than share public goods with Black Americans.

From the 1930s until the late ’60s, Democrats dominated national politics. They used their power to pass sweeping progressive legislation that transformed the American economy. But their coalition, which included southern Dixiecrats as well as northern liberals, fractured after President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Richard Nixon’s “southern strategy” exploited that rift and changed the electoral map. Since then, no Democratic presidential candidate has won a majority of the white vote.

Crucially, the civil-rights revolution also changed white Americans’ economic attitudes. In 1956, 65 percent of white people said they believed the government ought to guarantee a job to anyone who wanted one and to provide a minimum standard of living. By 1964, that number had sunk to 35 percent. Ronald Reagan eventually channeled that backlash into a free-market message by casting high taxes and generous social programs as funneling money from hardworking (white) Americans to undeserving (Black) “welfare queens.” In this telling, which has become popular on the left, Democrats are the tragic heroes. The mid-century economy was built on racial suppression and torn apart by racial progress. Economic inequality was the price liberals paid to do what was right on race.

The New York Times writer David Leonhardt is less inclined to let liberals off the hook. His new book, Ours Was the Shining Future, contends that the fracturing of the New Deal coalition was about more than race. Through the ’50s, the left was rooted in a broad working-class movement focused on material interests. But at the turn of the ’60s, a New Left emerged that was dominated by well-off college students. These activists were less concerned with economic demands than issues like nuclear disarmament, women’s rights, and the war in Vietnam. Their methods were not those of institutional politics but civil disobedience and protest. The rise of the New Left, Leonhardt argues, accelerated the exodus of white working-class voters from the Democratic coalition.

[David Leonhardt: The hard truth about immigration]

Robert F. Kennedy emerges as an unlikely hero in this telling. Although Kennedy was a committed supporter of civil rights, he recognized that Democrats were alienating their working-class base. As a primary candidate in 1968, he emphasized the need to restore “law and order” and took shots at the New Left, opposing draft exemptions for college students. As a result of these and other centrist stances, Kennedy was criticized by the liberal press—even as he won key primary victories on the strength of his support from both white and Black working-class voters.

But Kennedy was assassinated in June that year, and the political path he represented died with him. That November, Nixon, a Republican, narrowly won the White House. In the process, he reached the same conclusion that Kennedy had: The Democrats had lost touch with the working class, leaving millions of voters up for grabs. In the 1972 election, Nixon portrayed his opponent, George McGovern, as the candidate of the “three A’s”—acid, abortion, and amnesty (the latter referring to draft dodgers). He went after Democrats for being soft on crime and unpatriotic. On Election Day, he won the largest landslide since Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936. For Leonhardt, that was the moment when the New Deal coalition shattered. From then on, as the Democratic Party continued to reflect the views of college graduates and professionals, it would lose more and more working-class voters.

McGhee’s and Leonhardt’s accounts might appear to be in tension, echoing the “race versus class” debate that followed Trump’s victory in 2016. In fact, they’re complementary. As the economist Thomas Piketty has shown, since the’60s, left-leaning parties in most Western countries, not just the U.S., have become dominated by college-educated voters and lost working-class support. But nowhere in Europe was the backlash quite as immediate and intense as it was in the U.S. A major difference, of course, is the country’s unique racial history.

The 1972 election might have fractured the Democratic coalition, but that still doesn’t explain the rise of free-market conservatism. The new Republican majority did not arrive with a radical economic agenda. Nixon combined social conservatism with a version of New Deal economics. His administration increased funding for Social Security and food stamps, raised the capital-gains tax, and created the Environmental Protection Agency. Meanwhile, laissez-faire economics remained unpopular. Polls from the ’70s found that most Republicans believed that taxes and benefits should remain at present levels, and anti-tax ballot initiatives failed in several states by wide margins. Even Reagan largely avoided talking about tax cuts during his failed 1976 presidential campaign. The story of America’s economic pivot still has a missing piece.]

According to the economic historian Gary Gerstle’s 2022 book, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order, that piece is the severe economic crisis of the mid-’70s. The 1973 Arab oil embargo sent inflation spiraling out of control. Not long afterward, the economy plunged into recession. Median family income was significantly lower in 1979 than it had been at the beginning of the decade, adjusting for inflation. “These changing economic circumstances, coming on the heels of the divisions over race and Vietnam, broke apart the New Deal order,” Gerstle writes. (Leonhardt also discusses the economic shocks of the ’70s, but they play a less central role in his analysis.)

Free-market ideas had been circulating among a small cadre of academics and business leaders for decades—most notably the University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman. The ’70s crisis provided a perfect opening to translate them into public policy, and Reagan was the perfect messenger. “Government is not the solution to our problem,” he declared in his 1981 inaugural address. “Government is the problem.”

Part of Reagan’s genius was that the message meant different things to different constituencies. For southern whites, government was forcing school desegregation. For the religious right, government was licensing abortion and preventing prayer in schools. And for working-class voters who bought Reagan’s pitch, a bloated federal government was behind their plummeting economic fortunes. At the same time, Reagan’s message tapped into genuine shortcomings with the economic status quo. The Johnson administration’s heavy spending had helped ignite inflation, and Nixon’s attempt at price controls had failed to quell it. The generous contracts won by auto unions made it hard for American manufacturers to compete with nonunionized Japanese ones. After a decade of pain, most Americans now favored cutting taxes. The public was ready for something different.

[Eric Posner: Milton Friedman was wrong]

They got it. The top marginal income-tax rate was 70 percent when Reagan took office and 28 percent when he left. Union membership shriveled. Deregulation led to an explosion of the financial sector, and Reagan’s Supreme Court appointments set the stage for decades of consequential pro-business rulings. None of this, Gerstle argues, was preordained. The political tumult of the ’60s helped crack the Democrats’ electoral coalition, but it took the unusual confluence of a major economic crisis and a talented political communicator to create a new consensus. By the ’90s, Democrats had accommodated themselves to the core tenets of the Reagan revolution. President Bill Clinton further deregulated the financial sector, pushed through the North American Free Trade Agreement, and signed a bill designed to “end welfare as we know it.” Echoing Reagan, in his 1996 State of the Union address, Clinton conceded: “The era of big government is over.”

Today, we seem to be living through another inflection point in American politics—one that in some ways resembles the ’60s and ’70s. Then and now, previously durable coalitions collapsed, new issues surged to the fore, and policies once considered radical became mainstream. Political leaders in both parties no longer feel the same need to bow at the altar of free markets and small government. But, also like the ’70s, the current moment is defined by a sense of unresolved contestation. Although many old ideas have lost their hold, they have yet to be replaced by a new economic consensus. The old order is crumbling, but a new one has yet to be born.

The Biden administration and its allies are trying to change that. Since taking office, President Joe Biden has pursued an ambitious policy agenda designed to transform the U.S. economy and taken overt shots at Reagan’s legacy. “Milton Friedman isn’t running the show anymore,” Biden quipped in 2020. Yet an economic paradigm is only as strong as the political coalition that backs it. Unlike Nixon, Biden has not figured out how to cleave apart his opponents’ coalition. And unlike Reagan, he hasn’t hit upon the kind of grand political narrative needed to forge a new one. Current polling suggests that he may struggle to win reelection.

[Franklin Foer: The new Washington consensus]

Meanwhile, the Republican Party struggles to muster any coherent economic agenda. A handful of Republican senators, including J. D. Vance, Marco Rubio, and Josh Hawley, have embraced economic populism to some degree, but they remain a minority within their party.

The path out of our chaotic present to a new political-economic consensus is hard to imagine. But that has always been true of moments of transition. In the early ’70s, no one could have predicted that a combination of social upheaval, economic crisis, and political talent was about to usher in a brand-new economic era. Perhaps the same is true today. The Reagan revolution is never coming back. Neither is the New Deal order that came before it. Whatever comes next will be something new.

McGhee’s and Leonhardt’s accounts might appear to be in tension, echoing the “race versus class” debate that followed Trump’s victory in 2016. In fact, they’re complementary. As the economist Thomas Piketty has shown, since the’60s, left-leaning parties in most Western countries, not just the U.S., have become dominated by college-educated voters and lost working-class support. But nowhere in Europe was the backlash quite as immediate and intense as it was in the U.S. A major difference, of course, is the country’s unique racial history.

The 1972 election might have fractured the Democratic coalition, but that still doesn’t explain the rise of free-market conservatism. The new Republican majority did not arrive with a radical economic agenda. Nixon combined social conservatism with a version of New Deal economics. His administration increased funding for Social Security and food stamps, raised the capital-gains tax, and created the Environmental Protection Agency. Meanwhile, laissez-faire economics remained unpopular. Polls from the ’70s found that most Republicans believed that taxes and benefits should remain at present levels, and anti-tax ballot initiatives failed in several states by wide margins. Even Reagan largely avoided talking about tax cuts during his failed 1976 presidential campaign. The story of America’s economic pivot still has a missing piece.]

According to the economic historian Gary Gerstle’s 2022 book, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order, that piece is the severe economic crisis of the mid-’70s. The 1973 Arab oil embargo sent inflation spiraling out of control. Not long afterward, the economy plunged into recession. Median family income was significantly lower in 1979 than it had been at the beginning of the decade, adjusting for inflation. “These changing economic circumstances, coming on the heels of the divisions over race and Vietnam, broke apart the New Deal order,” Gerstle writes. (Leonhardt also discusses the economic shocks of the ’70s, but they play a less central role in his analysis.)

Free-market ideas had been circulating among a small cadre of academics and business leaders for decades—most notably the University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman. The ’70s crisis provided a perfect opening to translate them into public policy, and Reagan was the perfect messenger. “Government is not the solution to our problem,” he declared in his 1981 inaugural address. “Government is the problem.”

Part of Reagan’s genius was that the message meant different things to different constituencies. For southern whites, government was forcing school desegregation. For the religious right, government was licensing abortion and preventing prayer in schools. And for working-class voters who bought Reagan’s pitch, a bloated federal government was behind their plummeting economic fortunes. At the same time, Reagan’s message tapped into genuine shortcomings with the economic status quo. The Johnson administration’s heavy spending had helped ignite inflation, and Nixon’s attempt at price controls had failed to quell it. The generous contracts won by auto unions made it hard for American manufacturers to compete with nonunionized Japanese ones. After a decade of pain, most Americans now favored cutting taxes. The public was ready for something different.

[Eric Posner: Milton Friedman was wrong]

They got it. The top marginal income-tax rate was 70 percent when Reagan took office and 28 percent when he left. Union membership shriveled. Deregulation led to an explosion of the financial sector, and Reagan’s Supreme Court appointments set the stage for decades of consequential pro-business rulings. None of this, Gerstle argues, was preordained. The political tumult of the ’60s helped crack the Democrats’ electoral coalition, but it took the unusual confluence of a major economic crisis and a talented political communicator to create a new consensus. By the ’90s, Democrats had accommodated themselves to the core tenets of the Reagan revolution. President Bill Clinton further deregulated the financial sector, pushed through the North American Free Trade Agreement, and signed a bill designed to “end welfare as we know it.” Echoing Reagan, in his 1996 State of the Union address, Clinton conceded: “The era of big government is over.”

Today, we seem to be living through another inflection point in American politics—one that in some ways resembles the ’60s and ’70s. Then and now, previously durable coalitions collapsed, new issues surged to the fore, and policies once considered radical became mainstream. Political leaders in both parties no longer feel the same need to bow at the altar of free markets and small government. But, also like the ’70s, the current moment is defined by a sense of unresolved contestation. Although many old ideas have lost their hold, they have yet to be replaced by a new economic consensus. The old order is crumbling, but a new one has yet to be born.

The Biden administration and its allies are trying to change that. Since taking office, President Joe Biden has pursued an ambitious policy agenda designed to transform the U.S. economy and taken overt shots at Reagan’s legacy. “Milton Friedman isn’t running the show anymore,” Biden quipped in 2020. Yet an economic paradigm is only as strong as the political coalition that backs it. Unlike Nixon, Biden has not figured out how to cleave apart his opponents’ coalition. And unlike Reagan, he hasn’t hit upon the kind of grand political narrative needed to forge a new one. Current polling suggests that he may struggle to win reelection.

[Franklin Foer: The new Washington consensus]

Meanwhile, the Republican Party struggles to muster any coherent economic agenda. A handful of Republican senators, including J. D. Vance, Marco Rubio, and Josh Hawley, have embraced economic populism to some degree, but they remain a minority within their party.

The path out of our chaotic present to a new political-economic consensus is hard to imagine. But that has always been true of moments of transition. In the early ’70s, no one could have predicted that a combination of social upheaval, economic crisis, and political talent was about to usher in a brand-new economic era. Perhaps the same is true today. The Reagan revolution is never coming back. Neither is the New Deal order that came before it. Whatever comes next will be something new.

T

Törölt tag

Guest

Whoops!

This page doesn’t exist or can’t be found.

Ez gyors volt.

Whoops!

This page doesn’t exist or can’t be found.

Ez gyors volt.

Why America Abandoned the Greatest Economy in History

Was the country’s turn toward free-market fundamentalism driven by race, class, or something else? Yes.

Ez egy érdekes iromány, érdemes végigmenni rajta.

Why America Abandoned the Greatest Economy in History

Was the country’s turn toward free-market fundamentalism driven by race, class, or something else? Yes.www.theatlantic.com

A US-t belső szemmel nézi és közben megfeledkezik a világról, a környezetről, és a US ambíciók alakulásáról ebben a világban.

Ezeknek a kicsírázó ambícióknak jelentős visszahatása volt a belső gazdasági folyamatokra is.

A 24. hu a cikk utolsó mondatával öntökön lőtte magát.

Írják, hogy:

"És erre hogy reagált Musk? A milliárdos november 22-én egy, a témától teljesen független cikk, a „Három módszer, hogy a munkahelyünk igazságosabb legyen” című, alapvetően a sokszínűséget hirdető (értsd bevallottan a „túl fehér” munkahelyek és munkahelyi kultúra ellen küzdő – a szerk.) írás alá annyit kommentelt, hogy nagyon rasszista cikk a Forbstol."

Teljes mértéken igaz!

Az, hogy a 24 szerint alapvetően csak a sokszínűséget hirdette a firkász fekete csaj a "tudományos" cikkében, az egy ordas nagy ferdítés. Ti. egy az egyben a fehérek ellen agitált az egész firkálmányában. Mi ez ha nem szintiszta rasszizmus? Vagy a fehér az már nem is rasszizmus? Már nem is része a fehér ember a rasszoknak? S ha igen, az ellene indított támadás mi a nagyérdemű 24 tagsága szerint?

Az, hogy a 24-esek ehhez a legyünk sokszínűek, de ha lehet úgy, hogy a fehéreket kicsesszül, vagy elnyomjuk, állva és sikongva tapsikálnak az az ő gonoszságuk bizonyítéka. De hogy a normális embernek, aki ezt a cikket elolvassa belehetne adni azt, hogy ez csak egy alapvetően sokszínűséget hirdető írás, az több mint kétséges. Nagy a romlás, de egyre több értéke embernek nyílik ki a szeme.

Azonban ha az USA-ban ezen eszmék megerősödnek, az kb. az eddig fennálló minőségének a drasztikus romását fogja hozni Ti. az egyes álláshelyeket nem képesség és tudás alapján fogják betöltetni, hanem bőrszín alapján. Az pedig egy cégnek sem tesz jót, sőt az állami szerveknek sem. Gondoljunk bele, mi lesz ha a hadsereget egy csomó identitászavaros gyenge idegzetű személlyel töltik fel. Hogy fognak azok helyt állni egy Donbasz típusú fronton?

Vagy annyira biztosak az ottani fejesek, hogy az MI megoldja az alkalmazottak tudásának hiányát is? Nem lesz szükségük már konkrét alkotó és fenntartó szakikra?

Valószínű, hogy az USA azért meri megengedni ezt a színesítési luxust, mert bízik a nagy MI átállásban, amiben megint ő lesz az élen. De mi van ha nem jön össze és marad a sok színesített munkahely, ahol semmit sem fognak termelni.

Na mindegy is. Majd meglátjuk.

Eklatáns példa,Dél-Afrikában a néger kvóta,és hipp-hopp máris a tönk szélén vannak. De egy kicsit vissza menve ott van Rhodesia példája.A 24. hu a cikk utolsó mondatával öntökön lőtte magát.

Írják, hogy:

"És erre hogy reagált Musk? A milliárdos november 22-én egy, a témától teljesen független cikk, a „Három módszer, hogy a munkahelyünk igazságosabb legyen” című, alapvetően a sokszínűséget hirdető (értsd bevallottan a „túl fehér” munkahelyek és munkahelyi kultúra ellen küzdő – a szerk.) írás alá annyit kommentelt, hogy nagyon rasszista cikk a Forbstol."

Teljes mértéken igaz!

Az, hogy a 24 szerint alapvetően csak a sokszínűséget hirdette a firkász fekete csaj a "tudományos" cikkében, az egy ordas nagy ferdítés. Ti. egy az egyben a fehérek ellen agitált az egész firkálmányában. Mi ez ha nem szintiszta rasszizmus? Vagy a fehér az már nem is rasszizmus? Már nem is része a fehér ember a rasszoknak? S ha igen, az ellene indított támadás mi a nagyérdemű 24 tagsága szerint?

Az, hogy a 24-esek ehhez a legyünk sokszínűek, de ha lehet úgy, hogy a fehéreket kicsesszül, vagy elnyomjuk, állva és sikongva tapsikálnak az az ő gonoszságuk bizonyítéka. De hogy a normális embernek, aki ezt a cikket elolvassa belehetne adni azt, hogy ez csak egy alapvetően sokszínűséget hirdető írás, az több mint kétséges. Nagy a romlás, de egyre több értéke embernek nyílik ki a szeme.

Azonban ha az USA-ban ezen eszmék megerősödnek, az kb. az eddig fennálló minőségének a drasztikus romását fogja hozni Ti. az egyes álláshelyeket nem képesség és tudás alapján fogják betöltetni, hanem bőrszín alapján. Az pedig egy cégnek sem tesz jót, sőt az állami szerveknek sem. Gondoljunk bele, mi lesz ha a hadsereget egy csomó identitászavaros gyenge idegzetű személlyel töltik fel. Hogy fognak azok helyt állni egy Donbasz típusú fronton?

Vagy annyira biztosak az ottani fejesek, hogy az MI megoldja az alkalmazottak tudásának hiányát is? Nem lesz szükségük már konkrét alkotó és fenntartó szakikra?

Valószínű, hogy az USA azért meri megengedni ezt a színesítési luxust, mert bízik a nagy MI átállásban, amiben megint ő lesz az élen. De mi van ha nem jön össze és marad a sok színesített munkahely, ahol semmit sem fognak termelni.

Na mindegy is. Majd meglátjuk.

But Kennedy was assassinated in June that year, and the political path he represented died with him. That November, Nixon, a Republican, narrowly won the White House. In the process, he reached the same conclusion that Kennedy had: The Democrats had lost touch with the working class, leaving millions of voters up for grabs. In the 1972 election, Nixon portrayed his opponent, George McGovern, as the candidate of the “three A’s”—acid, abortion, and amnesty (the latter referring to draft dodgers). He went after Democrats for being soft on crime and unpatriotic. On Election Day, he won the largest landslide since Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936. For Leonhardt, that was the moment when the New Deal coalition shattered. From then on, as the Democratic Party continued to reflect the views of college graduates and professionals, it would lose more and more working-class voters.

McGhee’s and Leonhardt’s accounts might appear to be in tension, echoing the “race versus class” debate that followed Trump’s victory in 2016. In fact, they’re complementary. As the economist Thomas Piketty has shown, since the’60s, left-leaning parties in most Western countries, not just the U.S., have become dominated by college-educated voters and lost working-class support. But nowhere in Europe was the backlash quite as immediate and intense as it was in the U.S. A major difference, of course, is the country’s unique racial history.

The 1972 election might have fractured the Democratic coalition, but that still doesn’t explain the rise of free-market conservatism. The new Republican majority did not arrive with a radical economic agenda. Nixon combined social conservatism with a version of New Deal economics. His administration increased funding for Social Security and food stamps, raised the capital-gains tax, and created the Environmental Protection Agency. Meanwhile, laissez-faire economics remained unpopular. Polls from the ’70s found that most Republicans believed that taxes and benefits should remain at present levels, and anti-tax ballot initiatives failed in several states by wide margins. Even Reagan largely avoided talking about tax cuts during his failed 1976 presidential campaign. The story of America’s economic pivot still has a missing piece.]

According to the economic historian Gary Gerstle’s 2022 book, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order, that piece is the severe economic crisis of the mid-’70s. The 1973 Arab oil embargo sent inflation spiraling out of control. Not long afterward, the economy plunged into recession. Median family income was significantly lower in 1979 than it had been at the beginning of the decade, adjusting for inflation. “These changing economic circumstances, coming on the heels of the divisions over race and Vietnam, broke apart the New Deal order,” Gerstle writes. (Leonhardt also discusses the economic shocks of the ’70s, but they play a less central role in his analysis.)

Free-market ideas had been circulating among a small cadre of academics and business leaders for decades—most notably the University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman. The ’70s crisis provided a perfect opening to translate them into public policy, and Reagan was the perfect messenger. “Government is not the solution to our problem,” he declared in his 1981 inaugural address. “Government is the problem.”

Part of Reagan’s genius was that the message meant different things to different constituencies. For southern whites, government was forcing school desegregation. For the religious right, government was licensing abortion and preventing prayer in schools. And for working-class voters who bought Reagan’s pitch, a bloated federal government was behind their plummeting economic fortunes. At the same time, Reagan’s message tapped into genuine shortcomings with the economic status quo. The Johnson administration’s heavy spending had helped ignite inflation, and Nixon’s attempt at price controls had failed to quell it. The generous contracts won by auto unions made it hard for American manufacturers to compete with nonunionized Japanese ones. After a decade of pain, most Americans now favored cutting taxes. The public was ready for something different.

[Eric Posner: Milton Friedman was wrong]

They got it. The top marginal income-tax rate was 70 percent when Reagan took office and 28 percent when he left. Union membership shriveled. Deregulation led to an explosion of the financial sector, and Reagan’s Supreme Court appointments set the stage for decades of consequential pro-business rulings. None of this, Gerstle argues, was preordained. The political tumult of the ’60s helped crack the Democrats’ electoral coalition, but it took the unusual confluence of a major economic crisis and a talented political communicator to create a new consensus. By the ’90s, Democrats had accommodated themselves to the core tenets of the Reagan revolution. President Bill Clinton further deregulated the financial sector, pushed through the North American Free Trade Agreement, and signed a bill designed to “end welfare as we know it.” Echoing Reagan, in his 1996 State of the Union address, Clinton conceded: “The era of big government is over.”

Today, we seem to be living through another inflection point in American politics—one that in some ways resembles the ’60s and ’70s. Then and now, previously durable coalitions collapsed, new issues surged to the fore, and policies once considered radical became mainstream. Political leaders in both parties no longer feel the same need to bow at the altar of free markets and small government. But, also like the ’70s, the current moment is defined by a sense of unresolved contestation. Although many old ideas have lost their hold, they have yet to be replaced by a new economic consensus. The old order is crumbling, but a new one has yet to be born.

The Biden administration and its allies are trying to change that. Since taking office, President Joe Biden has pursued an ambitious policy agenda designed to transform the U.S. economy and taken overt shots at Reagan’s legacy. “Milton Friedman isn’t running the show anymore,” Biden quipped in 2020. Yet an economic paradigm is only as strong as the political coalition that backs it. Unlike Nixon, Biden has not figured out how to cleave apart his opponents’ coalition. And unlike Reagan, he hasn’t hit upon the kind of grand political narrative needed to forge a new one. Current polling suggests that he may struggle to win reelection.

[Franklin Foer: The new Washington consensus]

Meanwhile, the Republican Party struggles to muster any coherent economic agenda. A handful of Republican senators, including J. D. Vance, Marco Rubio, and Josh Hawley, have embraced economic populism to some degree, but they remain a minority within their party.

The path out of our chaotic present to a new political-economic consensus is hard to imagine. But that has always been true of moments of transition. In the early ’70s, no one could have predicted that a combination of social upheaval, economic crisis, and political talent was about to usher in a brand-new economic era. Perhaps the same is true today. The Reagan revolution is never coming back. Neither is the New Deal order that came before it. Whatever comes next will be something new.

Még a Reagan- és Clinton-korszakban is magasabb volt az átlagamerikai életszínvonala, mint ma.

Al Bundy (Rém Rendes Családban) 5,8 dolláros órabérben dolgozott, a korabeli minimálbér az államában 4,25 dollár volt. Geekek kiszámolták, a korabeli árak mellett igazából reális hogyha nem is konkrétan a sorozatban szereplőt, de egy saját házat megengedhetett magának, csak a hiteltörlesztés miatt kellett spórolnia:

A USA-ben a 70-es évek óta stagnál a bérek reálértéke, míg bizonyos dolgok, mint az ingatlan árak vagy az egyetemi tandíjak nagyon elszálltak, annyira, hogy sok ember annyira irreálisnak gondolja a 30-40 évvel ezelőtt életszinvonalat, hogy azt hiszi, csak a sitcomban volt lehetséges, hogy a cipőbolti eladónak saját emeletes háza legyen (3 hálószobával és 2 fürdőszobával, ahogy az amcsik számolnak), mégpedig úgy, hogy a felesége nem is dolgozik... Talán így is enyhén irreális, de nem annyira, mint ma hiszik.

Al Bandy azt a csinos tékozló feleséget, Peggyt nem engedhette meg magának, nélküle tök jól el lett volna, mint cipőbolti eladó.Még a Reagan- és Clinton-korszakban is magasabb volt az átlagamerikai életszínvonala, mint ma.

Al Bundy (Rém Rendes Családban) 5,8 dolláros órabérben dolgozott, a korabeli minimálbér az államában 4,25 dollár volt. Geekek kiszámolták, a korabeli árak mellett igazából reális hogyha nem is konkrétan a sorozatban szereplőt, de egy saját házat megengedhetett magának, csak a hiteltörlesztés miatt kellett spórolnia:

A USA-ben a 70-es évek óta stagnál a bérek reálértéke, míg bizonyos dolgok, mint az ingatlan árak vagy az egyetemi tandíjak nagyon elszálltak, annyira, hogy sok ember annyira irreálisnak gondolja a 30-40 évvel ezelőtt életszinvonalat, hogy azt hiszi, csak a sitcomban volt lehetséges, hogy a cipőbolti eladónak saját emeletes háza legyen (3 hálószobával és 2 fürdőszobával, ahogy az amcsik számolnak), mégpedig úgy, hogy a felesége nem is dolgozik... Talán így is enyhén irreális, de nem annyira, mint ma hiszik.

Emlékezzünk csak vissza, hogy is kezdődött mindig a sorozat: Al ül a kanapén és osztogatja mindenkinek a pénzt. Kap a lánya, a fia, az asszony és végül még a kutya is.Még a Reagan- és Clinton-korszakban is magasabb volt az átlagamerikai életszínvonala, mint ma.

Al Bundy (Rém Rendes Családban) 5,8 dolláros órabérben dolgozott, a korabeli minimálbér az államában 4,25 dollár volt. Geekek kiszámolták, a korabeli árak mellett igazából reális hogyha nem is konkrétan a sorozatban szereplőt, de egy saját házat megengedhetett magának, csak a hiteltörlesztés miatt kellett spórolnia:

A USA-ben a 70-es évek óta stagnál a bérek reálértéke, míg bizonyos dolgok, mint az ingatlan árak vagy az egyetemi tandíjak nagyon elszálltak, annyira, hogy sok ember annyira irreálisnak gondolja a 30-40 évvel ezelőtt életszinvonalat, hogy azt hiszi, csak a sitcomban volt lehetséges, hogy a cipőbolti eladónak saját emeletes háza legyen (3 hálószobával és 2 fürdőszobával, ahogy az amcsik számolnak), mégpedig úgy, hogy a felesége nem is dolgozik... Talán így is enyhén irreális, de nem annyira, mint ma hiszik.

Inkább a demokraták örülhetnek – tanulságos választások az USA-ban

Inkább a demokraták örülhetnek – tanulságos választások az USA-ban

Viccesnek tűnik ez az al bundy-s példa, de a legtöbb 40-50-es sajnos nem érti... sőt.. személyes támadásnak veszi ha azt mondja egy fiatal neki, hogy az Ő idejében könnyebb volt érvényesülni.

36 éve kezdődött a sorozat.

Elhiszem, hogy szarul hangzik, de a tények makacs dolgok!

36 éve kezdődött a sorozat.

Elhiszem, hogy szarul hangzik, de a tények makacs dolgok!

Mondjuk az eros tevedes, hogy a Reagan miatt lett volna, sokkal inkabb o verte szet pont azt a stabil, szakszervezeti stb rendszert, amelyikben az Al Bundy is hazat vett stb.Emlékezzünk csak vissza, hogy is kezdődött mindig a sorozat: Al ül a kanapén és osztogatja mindenkinek a pénzt. Kap a lánya, a fia, az asszony és végül még a kutya is.

A 90-es evekre elkezdett iszonyatosan kinyilni az ollo a vezeto beosztasuak es a koznep kozott, es mara mar csak az olyan, szabalyos mafiakkal rendelkezo "szakszervezetek" tagjai kepesek sokat keresni, mint a gatlastalanul tulorakat hamisito rendorok, a gyartas szunetelese eseten is 75% penzt kapo autogyariak es meg par hasonlo. Mindenki masnak shut up or there's the door, pal.

Ez amugy feljebb is megvan: kb tiz eve valtam meg nagyon jol fizeto allastol, mert nem birtak elfogadni, hogy semmi kedvem ket kisgyerek mellett korbeturnezni az osszes leanyceget North Americaban es egyesevel modernizalni mindenhol mindent 1-2 honap alatt (US West Coast, Florida, Vancouver stb); ezek utan addig noveltek az extra oraimat, hogy keptelenseg volt tovabb maradni (mondjuk pont emiatt pimaszul lehetett keresni, szoval a penzre nem volt panasz).